Let's take a walk. Where are we going? I dunno... away from here. Ok, but in which direction? We can take a walk for the pure pleasure of walking, seeing either new or familiar sites. I walked here to get coffee and write this. What do you wanna do?

History is a story we tell to explain why things happened and how we got where we are today. It's a path that we draw after the fact based on what we remember, anchored in major events that give a clear explanation for different twists and turns. Western art history primarily uses paintings to tell theses stories (sculptures, for some reason, tend to appear as secondary until modern art). Someone like Monet is important to the story because his paintings are especially illustrative of a point in the trajectory, specifically of Impressionist painting. Many other people were painting in the same style, but it seems like his series of the same view of the same scene, a church or some haystacks, at different times of day and weather conditions makes the idea of Impressionistic painting clear: quickly recording dapples of light rather than rendering solid objects.

It's not hard to see how the story of Western art history is used today to prop up certain kinds of work, inflate their financial value, and to dismiss other work as seemingly disconnected. But I feel drawn to find use in it, like Amy Silman exploring her attachment to Abstract Expressionism in "Ab-ex and Disco Balls", despite its image as a hetero/masculine style. For better or worse, this framework is how I came to understand art and what much of the contemporary art world is built on. While I agree we should work to move away from all of the problems this history creates, I don't think that the forms and stories it creates are inherently bad. We can learn from it and take what's useful and leave what's not. This is a cornerstone of any queer way of working with dominant culture.

What I'm proposing is that we can use this form of telling a story through a series of works to build a path to travel somewhere else, out of whatever the current dominant way of thinking demands.

"Ok, you still haven't said where we are going! And what's a walking simulator??"

Walking simulator, depending on who you ask, can be a loaded term. In my less dramatic formulation, it describes a genre of indie videogame where the primary action is walking through a space. I'm not here to track the definition and don't particularly care about the boundaries of the genre aside from noting first that I am attracted to it, and second that it represents a flash-point of excitement about what a videogame could be. In this essay I am going to use its detachment from a dominant mode of game design towards somewhere unknown and exciting. As you may have guessed, the walking simulator's primary transgression in game design is that "walking through a space" doesn't sound like much of a game. What's the goal? "Who's it versus?" Again, I don't really care if it's a game or not, but it uses videogame engines and looks like a videogame so either way they are in close dialogue.

I find terms like "videogame" or "art" useful as gravitational points. Similar to how gender is a spectrum (I like to think of it as a high-dimensional shape), these genres are just conventions that have a particular history and weight to them. To me as an artist, these rules for what art or games should look like are a place to play inside of, sometimes following the rules and sometimes breaking them. Getting closer to one pole makes a work more legible in a certain way, which has both advantages and disadvantages. Get sucked in too much and there is nowhere to move, all nuance is flattened. Fly too far out and you leave a lot of people behind. Luckily, we have the handy tool of creating historical paths so that we can take other people along for the ride out into the unknown.

So what will this path look like?

I'm going to map videogames to art historical points to construct my own energetic trajectory about where walking simulators came from, where they are now and imagine where they could go next. It doesn't matter if these games are in chronological order or if they have any actual influence on one another. I'm not that kind of historian! What's important is that it tells a story that makes sense that you can follow. What matters is that we go together.

Before diving in, I also want to note how both the Western art history story and walking simulators are centered on landscape. This art history is, to make a generalization, a story of how we got to totally abstract art like minimalism, which purposely avoids being read as representing an image like a landscape or portrait does. It gives a framework for appreciating abstract art as being just as rigorous, interesting, and integral to our lives as representational art. Similarly, my path of walking simulator history goes from the representational to the totally abstract and then into the dynamic space of contemporary image making. This is using art as an orientation device to move away from conventional videogames. But, I feel the need to stress that my goal is not simply moving from games to art (for more on how I understand art + games see my previous essay). Hopefully, this can cause a slingshot effect to fling us somewhere new- gravitational forces to playfully induce sustained movement so that we don't get stuck over there instead of being stuck right here.

I also want to clarify that I don't read the path of history as one of progress from less to more sophisticated. I find it a bit delusional to think that I, or anyone else alive right now, could come up with something that truly hasn't been thought of before after billions of other people. In my formulation, the historical story is just tracing a shift in expectations and legibility. Work at any point in Western art history is in that history because it's considered good art emblematic of its context. What came after is exciting in contrast to the previous framework. It's only "better" in that it represents movement away from a perceived solidified culture. This feels especially relevant to how videogames are often evaluated in terms of their constantly evolving rendering capabilities for creating realistic images. Older games get read as "good for their time" or "we didn't know better". This, as well as the rapid obsolescence of videogames (can you easily play something made 10 years ago? How about 20?) reinforces this progress based model of videogame history.

My model probably doesn't solve any of those problems other than leveling the playing field- movement is based on some other criteria than time or technology. I'm looking for more potential, more energy, more possibilities. I don't want to be stuck. We all know now how important it is to be able to take a walk.

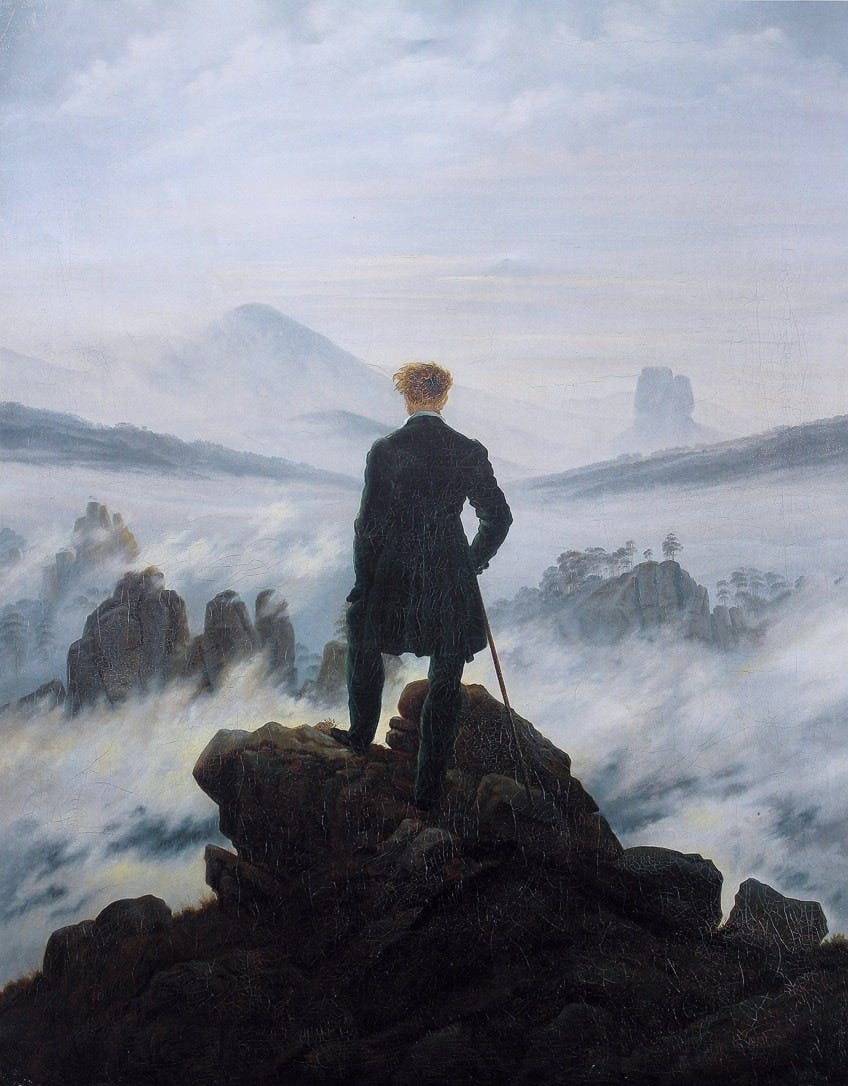

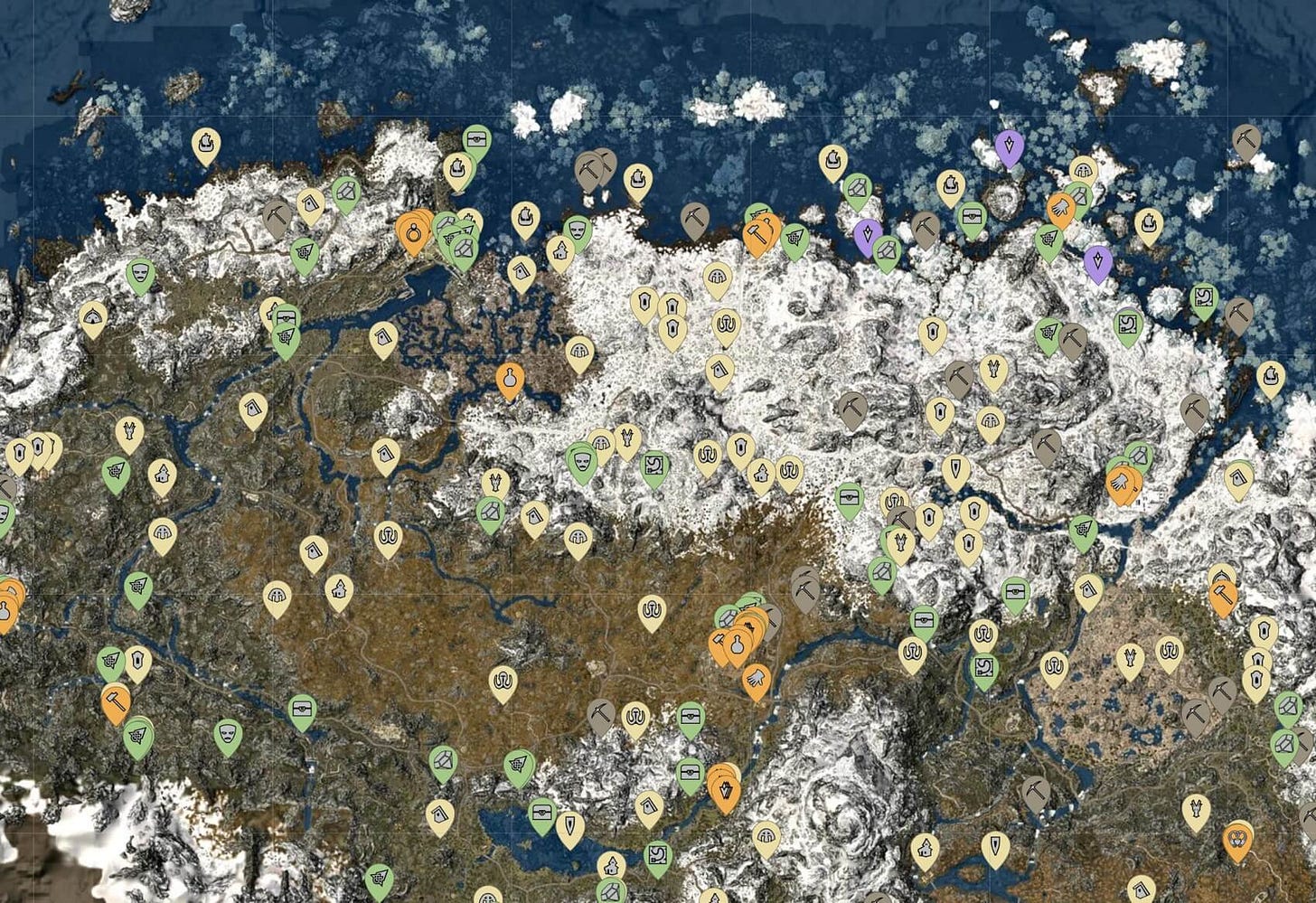

Skyrim - The Romantic Landscape

The first time I played Skyrim I immediately took a long walk. I had seen online that there was a wizard school in the northeast, and I was enough of a Harry Potter child to be immediately drawn in that direction. It was a long walk. I didn't know anything else about the game, so I didn't know that I could pay a small fee to ride a horse drawn cart and essentially teleport there. Instead I spent a few hours walking, avoiding monsters that were too strong for my freshly minted character to battle, and hoping I wasn't wasting my time.

Skyrim is one of the most successful games of the 2010's, having been re-released multiple times across different game consoles and with a still active online modding community. As such, it seems like a safe assumption to make that it is exemplary of what’s commonly considered a good videogame. It can be played for hundreds or even thousands of hours, features seemingly endless amounts of content, and can be played with a wide variety of strategies.

Walking in Skyrim often feels like an obstacle, sometimes a challenge or dare, sometimes as a punishment and incentive for advancing your character's abilities. you can instantly teleport to any place you've already been as a way of rewarding the player for exploring. Once you visit somewhere you can avoid the pesky activity of walking.

Despite the way walking can feel like friction, one of the most impressive feats of the game, especially for when it was released in 2011, is the amount of seamless detail of landscapes as you explore. There are many moments that aim at emulating the feeling of a sublime romantic landscape: a valley with a deep river, a snow covered mountain side, a wide open grassy field, a deep, dark cavern... In the game this wilderness is potentially dangerous, especially as a player with no experience with a character who has no power. Later in the game, just being outside could randomly trigger a hostile dragon to appear. Ironically, in this first play-through of mine I was so wrapped up in pursuing the wizard college that I fully neglected to do any of the main story plot and therefore never saw any dragon, despite that being one of the main points of the game.

Another series of mishaps- while trying to go back to the main story line I was handing another character an important object that he asked for and was interrupted by someone walking in to arrest me. A glitch happened- I no longer possessed the item but the next sequence of events had not been triggered. The main plot was stuck, and I didn't know that I should have had a backup save file because of bugs exactly like this. Having not learned my lesson, I went to start a new game to actually do the main story line, and then accidentally saved over my original save file. The record of me walking for over 100 hours was erased.

The glitches in Skyrim are part of its charm. It shows that the game is slightly too big, a fact of power that the developers packed so much content in that it would have had to be much smaller for the bugs not to exist. But a glitch is always also an opening, a sign that things that are read as broken, mistakes, or unfinished from production standards are not only potentially fun and/or beautiful but also maybe even better than the original, intended play. Maybe, we can follow them out of the main plot of videogame design and see where they lead us.

Dear Esther and Gone Home: Reductive Realism

Ironically, the next step on my walking simulator history path is in the opposite direction, to two indie games which deflate the romantic fantasy of Skyrim into something that feels more real to life. An illustration of this in Western art history is clear if you compare, for example, J.M.W. Turner's seascapes to Daumier's "Third Class Carriage". The drama, grandness, danger, and fluidity of nature is replaced by a crisp, stark, muted image of a "regular person" (meaning not someone rich, biblical, or mythological).

Dear Esther is a game that looks like Skyrim. Whether or not this was an intentional reference or a coincidence of what videogames tend to look like, the sheer dominance of Skyrim as a standard makes it feel intimately related. However, this is Skyrim deflated. There is one story line, one pat, and no action besides walking and looking. A story unfolds as you move forward, and then its over. there is still a romantic quality to the story of being on a remote island in another time. But The scale of the story is a few people. It feels personal.

Gone Home takes this a step further and places you in a typical suburban home. While there is some more typical game play in the form of puzzles, it still is a linear story revealed by walking. The dramatic conventions of the videogame are revealed to you as a conditioned response, like expecting a dragon to pop out at any moment, and incorporates it into a story about coming out and falling in love. This is the walking simulator as representational narrative. A play about "real life". The unexpected moments feel highly designed. The puzzles and story bits are intentionally placed for you to stumble into.

These two games are still only a step away from the dominating gravity of Skyrim- they were made by production teams and were commercially successful. A conversation was sparked by them into conceptualizing walking simulators as a new genre. Part of this discourse was the history of the term as being a mean joke, angry gamers saying "this isn't a Real Game." This is an interesting inflection point to see the birth of a genre- like astronomers finding a star being born. Will it stabilize and gain a powerful gravity? Probably not, but it is still known by people and inspires a certain kind of game to be made that feels legitimate, to most, and accessible to more developers. For my purposes it's a significant stepping stone away from the center of games and going in a new direction.

Proteus: Cezanne's Modern Turn

In terms of production and success this one is a lateral move. Proteus is to me a perfect example of what a walking simulator could be. The game is completely non-verbal, no written or spoken words just visuals and music. You walk as an unspecified, floating observer of an island landscape of chunky, pixelated trees and animals. It's a cartoony visual style that occasionally, through the large pixels size, verges on abstraction. But everything is still identifiable as a specific representation of an object: a tree, a crab, a meteor shower, ect.

In Western art history this turn to abstraction is often illustrated by Cezanne, who painted the same landscape and slowly took it from realistic to simplified shapes. We still know its a mountain, but that’s because we know he paints mountains.

The story in Proteus similarly teeters on abstraction- the ending, where the camera floats up into the sky and then closes with an eyelid shape, implies that you may have been one of the small spirits you saw and followed from level to level. It's vague enough that this is an interpretation and not a definitive reading, but there's enough representation happening that the story, in it's most mundane explanation, is that you are walking on an island. The story and visuals and action are still snug inside the frame. You can explore, but there is still a linear narrative- the progression of the four seasons.

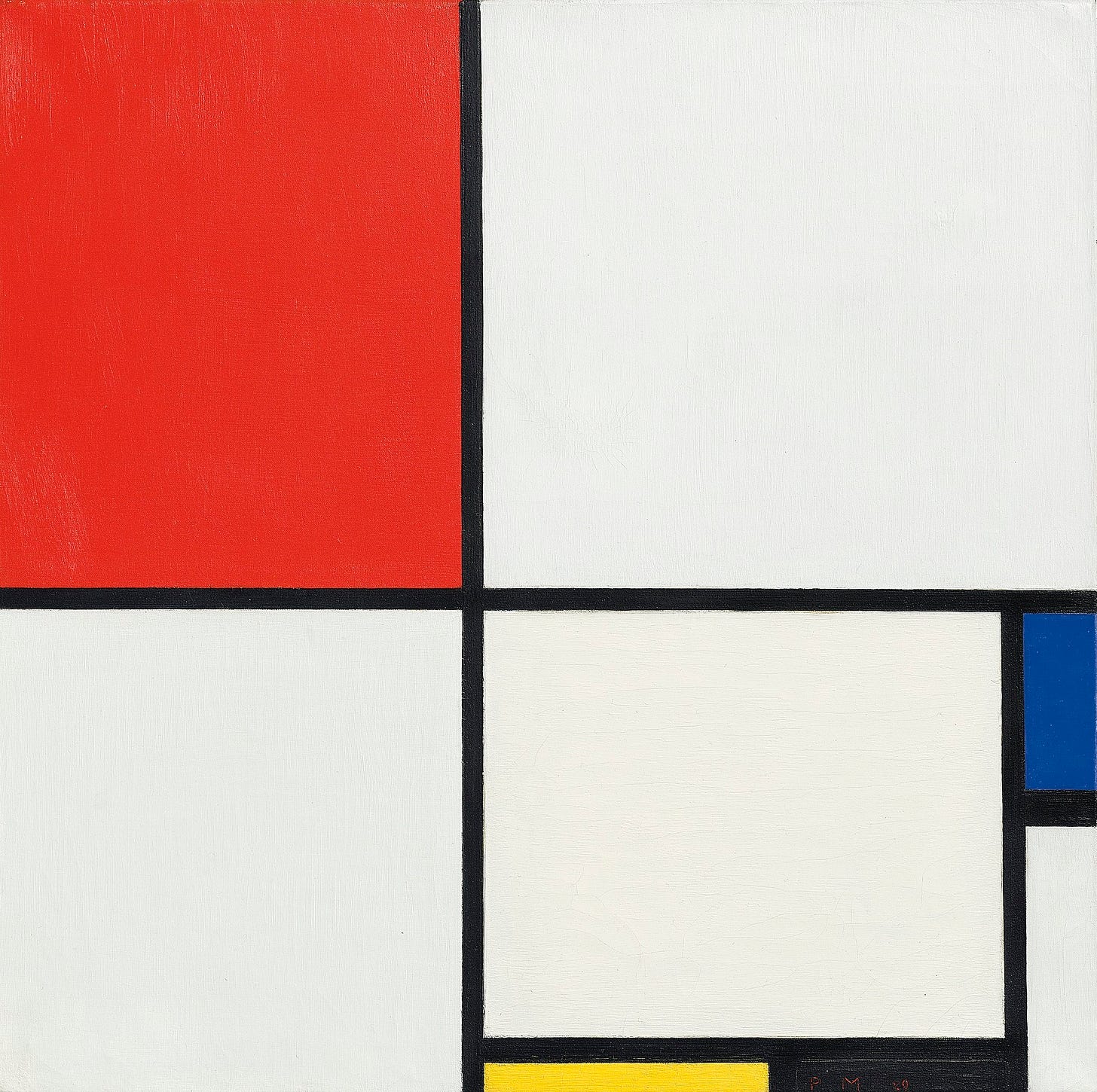

A Cosmic Forest: Mondrian's Flattening Abstraction

Mondrian's paintings have this funny place in our popular imagination as famous, important paintings that are instantly recognizable but simultaneously invokes a response of, "I could do that." In this simplified art history story, they are important as a moment where painting was allowed to be completely abstract and flat-- they aren't an attempt to depict another object or to create the illusion of depth or perspective. (Incidentally, from what I've seen of his other paintings he arrived here while painting abstract tree branches.)

For videogames, depth and representation are important tools for easily communicating to a player what they are doing. If you show me an image where I see a room of threatening people and I see my avatar holding a gun, I can easily assume that what I need to do is attack these people before they attack me. I then use my memory of previous games I've played like this and use that knowledge to press buttons on the controller to initiate these actions. By having a sense of depth in the room I can navigate my camera/avatar through the space. Having both a clear sense of space and of what images on the screen represent are essential to this game design. If the player has to stop and figure out what something is it throws them out of the flow of play.

I suspect that this is why true abstraction is antithetical to game design and why it's practically absent from the form. There is a strong genre of especially mobile games that are abstract in the sense that its just blocks or balls with numbers on them. While I find this interesting, it feels like for this walk its the wrong path, probably because it is so goal oriented-- the abstract shapes are directly tied to numbers that represent scores and obstacles.

A Cosmic Forest, similar to Dear Esther referencing Skyrim, feels to me in deep conversation with Proteus to the point where it feels like an intentional referent. The main differences here are that there is no ground, progressing in the story is so specific and hard to follow that it feels beside the point of the game, and that the "trees" of the "forest" are just horizontal bands of color with no shading. Space is created through a fog effect, where more distant shapes are tinted with white. Often, you get lost in undifferentiated bands of color. The screen becomes a flat surface with no depth and a flicker of complete abstraction. If we didn't have the "forest" in the title we probably wouldn't feel sure calling the bands trees. These environments make orientation in the game feel almost impossible, and for me that experiences is exactly what makes it so exciting. It's still the same format as Proteus, but the focus is shifted. Even if it's hard to find, there is still a way of walking through a linear story in this game.

Cornhub: Rauschenberg's Flatbed Picture Plane

Imagine walking in a videogame, but all you can see is corn. Every inch of space is occupied, there is no sense of left or right, but you can still tell up from down. Having a map would feel pointless, as you learn the space is just a rectangular platform when you fall off it it into the infinite digital void. Even if you knew where in that rectangle you were, what good would it do? There's nowhere to go, unless you want to fall of the edge. Cornhub is perhaps the most properly a walking simulator in this list, there is no goal or possibility other than walking and looking. There are no goals, no progression, just relentless corn. The fact that there’s a sense of up and down, as well as its place on this "history", gives it the sense of still being a landscape, although the corn is candy corn and not the plant you'd expect from a landscape.

In terms of abstraction, we seem to have ironically gone from the abstract shapes of Proteus and A Cosmic Forest back into representational images of candy corn, but this feels different. While the game is "about" corn, as the pun title confirms, it would be hard to saw that it functions as corn. You don't eat it, grow it, make it, sell it, process it, transport it, or any other action you might do with real corn. It's just there as an image filling your screen.

Something similar happens in the work of Robert Rauschenberg, who's paintings and sculptures are filled with images. But most of these are found and collaged, it's hard to say that he is "painting" these as subjects in the conventional sense, or that any of them are "about" the main images depicted. They all feel loose, hard to pin down. Art critic Leo Steinberg refers to this as the flatbed picture plane, where the images seem to sit on the surface of the paintings rather than act as illusionistic windows into a constructed world. The collaged images then act as a constellation of information and references. It's a collage that doesn't try to recompose into any logical sense of space, just images and images and images.

For my "history" of walking simulators, Cornhub is this moment where the game stops being concerned with representation to the point where, paradoxically, we don't need abstraction anymore to keep us going down the path. The computer screen is now a surface delivering our eyeballs information, not luring us into suspended belief about being in a fictional world doing fictional things. This feels more "real" in the sense that you are having literal interactions with digital objects with no imagination mediating the experience. It's just you and chaotic corn.

Oikospiel - Trecartin and Contemporary Art

Where the typical Western art history model we are scaffolding off of tends to fall apart is when we get to the present day. After all, this history is happening right now! It's hard to abstract a narrative about a moment that is still happening, and there are many artists, curator, collectors, and institutions jockeying to be put in the history books. It's also difficult because Western art has now become global art where many people around the world, connected by the internet and international art fairs, are interacting in ways that normally was confined to more local and specific scenes like New York in the 60's or Paris in the 30's.

But I'm not concerned here with historical accuracy, I've got places to go. So I'm not claiming that Ryan Trecartin is The contemporary artist, I just like his work a lot and think that it's undeniably contemporary and is interesting to look at next to Oikospiel, the last game in this historical walk.

Both Oikospiel and Trecartin's videos are hard to describe, so my first advice would be to watch clips of both because I won't do them justice and neither will still images.

In our previous step we had finally let an image back in, providing it was just an image and not pretending to be something more. Now we can open the floodgates and let Everything back in, maybe even be on the edge of letting too much in. Sorry if you have a headache now.

Oikospiel, created by David Kanaga, who also did the music for Proteus, is a game-opera where dogs are being hired to work on an infinite opera-game for Donkey Koch, and the dogs are attempting to unionize. You play the game both in the sense of playing a videogame but also in the way of playing an instrument or taking part in a play. Sometimes you are a dog walking through a landscape trying to move a plot forward, sometimes you are a computer mouse, or something triggering MIDI musical notes, and at one point you can read from several full length books that are sitting on a desk. You may be correctly thinking, we've circled around back to the beginning of our walk! I'm walking around completing tasks! And I agree, but also it's different because the game is unafraid to reference or not reference, put it in a blender, shit on it, vomit on it, give birth to it. It oscillates. Being on the other side of the flatbed picture plane, having many moments where the screen becomes a surface of information rather than a portal into a fictional world, it defamiliarizes the more conventional game moments. When we land in a carbon copy of the first level of Zelda: Ocarina of Time its presented to us simultaneously as a space to move around and as an image from an iconic game. You never get enough footing to feel settled into any illusion of space or fiction, the game pulls you into the screen just to push you back out again.

Ryan Trecartin and his collaborator Lizzie Fitch create film installations that similarly push and pull us in and out of weird spaces. They tend to have even less coherent plot than Oikospiel and feature characters that act as shifting archetypes who constantly say one-liners more to the camera than to each other. Imagine watching the "this season on Real Housewives" teaser reel but sped up 1.5X and it's 40 minutes long. Sure there are people, spaces, identities, objects... a lot of representation. Despite that, none of these things ever land with a solid meaning and, if they do, it probably will be upended or left behind in the next scene.

This isn't to say either Oikospiel or Trecartin's work are meaningless, they have very specifically chosen themes and references woven throughout. It's easy to mistake these swirling of intensities for being unserious. Surely topics like global warming, gender, labor, and globalization deserve more serious media than videogames, reality tv, and the internet? but I think it's a mistake to dismiss them for being silly, and these media choices are deeply reflective of how a lot of people spend their leisure time now. I also want to reiterate that I think these works and this "history" are just one possible route among infinite possibilities for us to travel in. Don't like it? Use this as a gravitational sling shot to wherever you wanna go. I have no specific direction in mind, I just like being able to move however feels right and is most exciting to me. At this point Skyrim is both far away and close by, we can imagine a game that folds it in as seamlessly as Oikospiel did Zelda. This history is an additive process, the end of the path isn't the best or most correct or most advanced. It might not even be the furthest away from the start. We could imagine this path forking off in different spots, looping around, and creating a Deleuzian rhizome. If we felt the need we could fast travel back to any node and go from there, the important thing is that we are mobile and not stuck in the vortex of dominant tastes and methods.

Thank you for taking this walk with me !