Abstract Videogames

This essay is being released in conjuction with Arcade Arcade at Bugsy LA on Sunday June 25, as part of my show “Render Me Visible”. RSVP at bugsy.la/rsvp for more info!

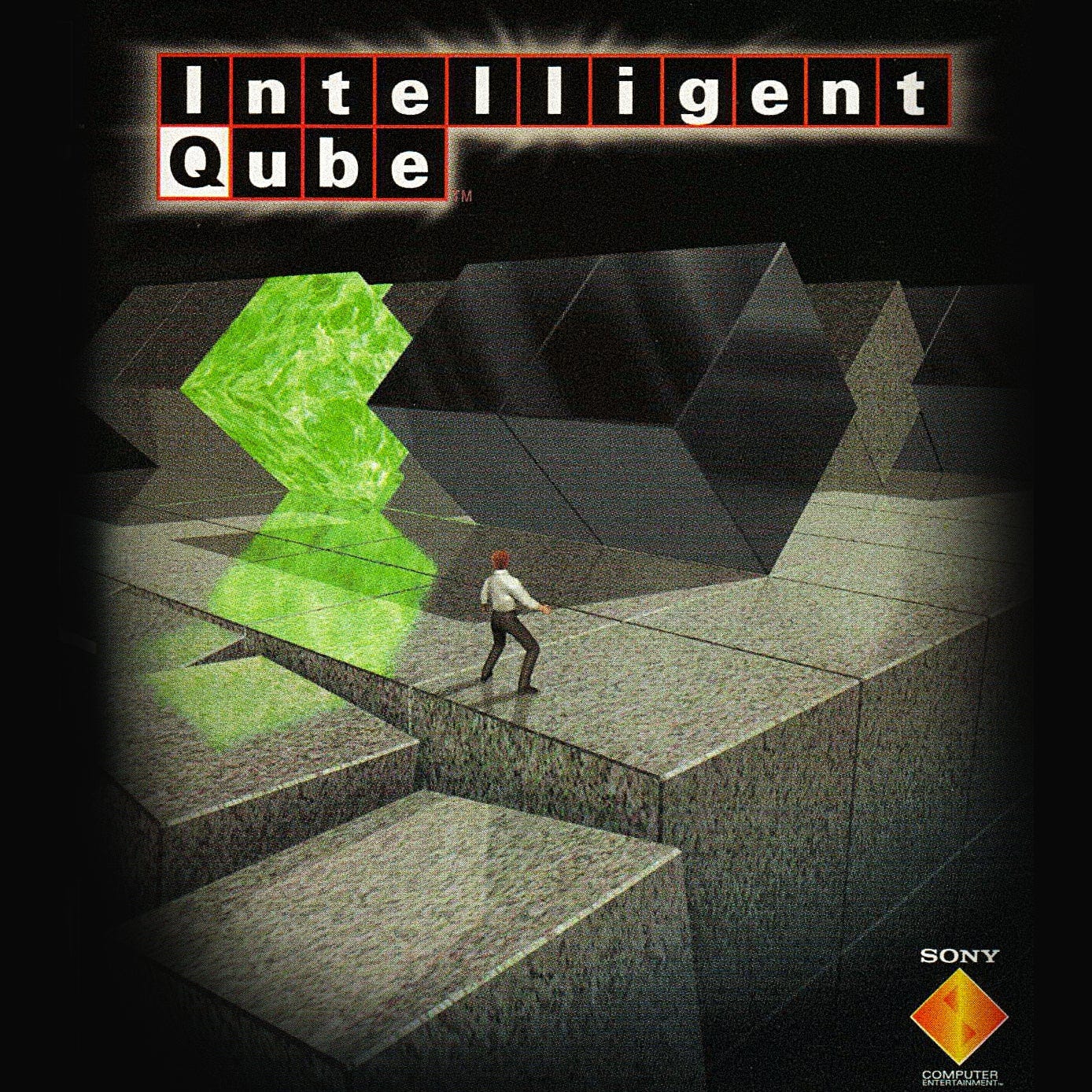

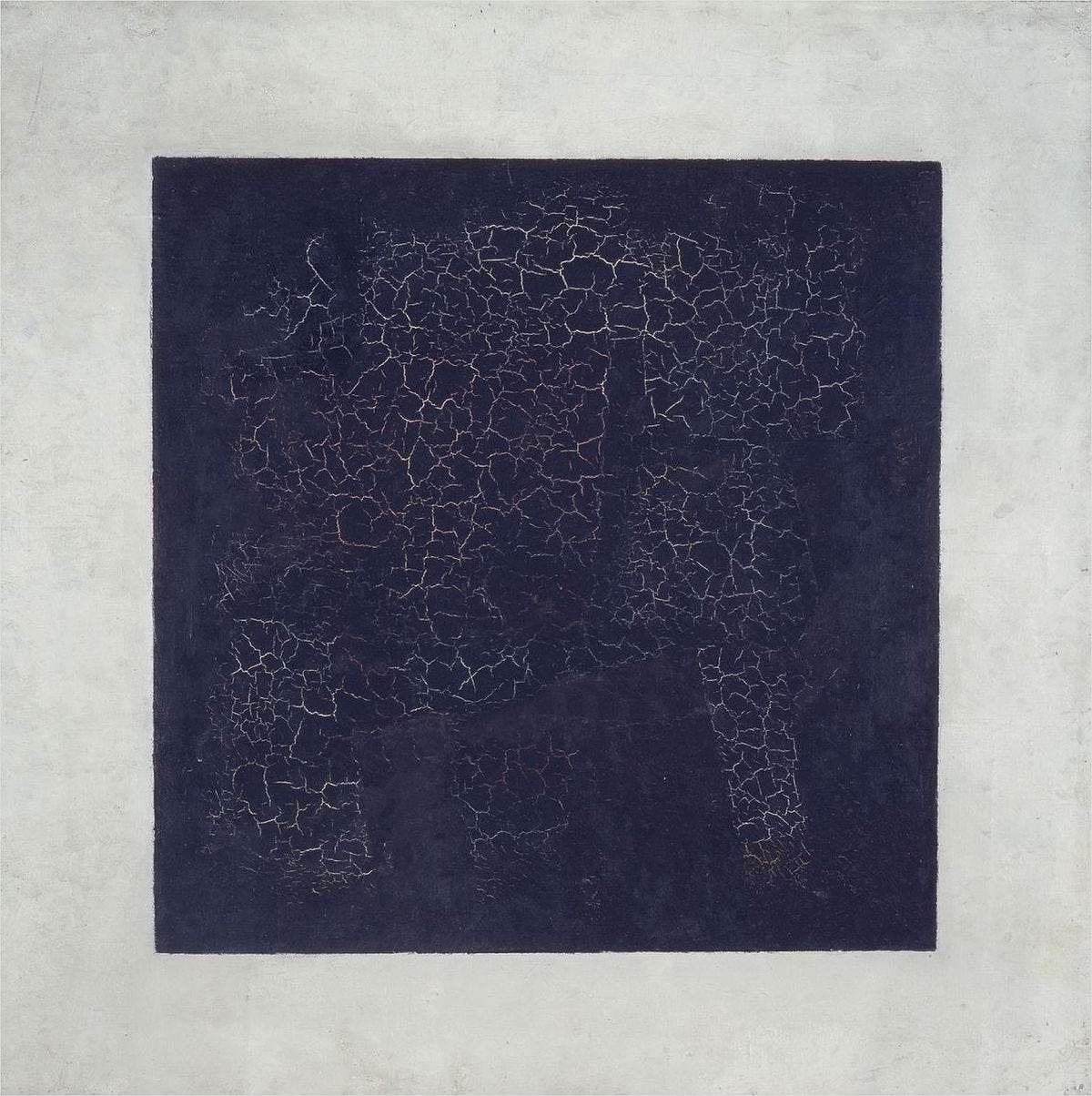

Where are the abstract videogames? Try to think of one. Can you? It's surprising how few there seem to be; especially considering that the default shape of the videogame engine and 3D modeling software is the cube, the iconic shape of abstract art. So why are games so stuck on representation?

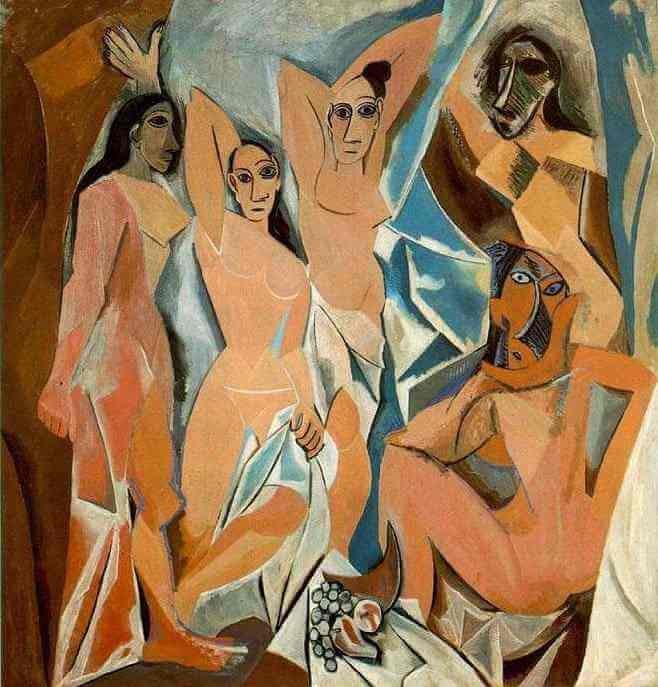

Now you might be asking, "Why do you want abstract games?" First I'd say just because I want it, and that desire is more than enough reason for me. This might be because of my love of modern art, which in Western art history is the point when painting and sculpture arrived (back?) at abstraction after centuries of figurative work depicting religious, historical, and royal scenes. While I was trying to process this narrative and understand the contemporary art of today, which has exploded into a vast array of ways of making art, I started using videogame technology to make art. Because of the default, simple geometry, I felt an immediate link between videogames and abstract art. However, I quickly found out that people react to this approach as inherently wrong and now it's become one of my main recurring questions as an artist.

Abstraction is embarrassing to computer graphics. It's a sign of "primitive" technology, not yet able to deliver on its promise of endless, immersive, responsive gaming. The history of the development of computer graphics reads like a race to realism; every new feature being one step closer to being able to create photographic realism. While videogames share this continued mission I think that their reliance on realism stemmed also from a design solution.

The earliest videogames created include OXO (tic-tac-toe), Tennis for Two, and Spacewar! The first two are games we already know and the third is immediately legible in its sci-fi narrative, shoot the other ship and don't fall into the star (today it reads as a black hole, but when Spacewar! was made astronomers were just figuring out they existed). Computers were not only brand new but expensive and hard to use, the idea of playing games on them wasn't on anyone's mind. If someone had attempted to make an abstract game with these computers it could have seemed like indiscernible nonsense to all but a small group of people. Tennis, spaceships, and tic-tac-toe we get. "Oh! Wow! That's what this machine can do?" As games grew into the industry they are now this design shorthand became the standard. It's easy to sell a game with a one-liner: you shoot each other, you're playing a sport, you are a cat, you have to match the blocks… The representational idea comes first, learning the interface comes second.

I want to be clear that I'm not saying this is bad or less sophisticated. Looking at art history, it's easy to see how calling an aesthetic more advanced than another is just a constructed perspective. Many of the "innovations" of modern art were ideas sparked by seeing existing art traditions like African masks or Japanese prints. What interests me about abstraction in games is that it's almost completely absent as a strategy. So, without claiming it's better or more sophisticated, I want to develop it as a viable path that has its own strengths and weaknesses.

What do I even mean by abstraction in games? For now, let's say it's images that are not representing something else. This immediately eliminates most games from the discussion. We're left with things like Tetris, whose shapes are just shapes and not pictures of another object, and a handful of mobile games that have clean, minimal aesthetics, and some indie/art games. But this doesn't feel right… If I'm trying to move away from a dominant method of game design it can't be toward popular mobile games, which at this point are only slightly different from slot machines. These games use abstraction as hyper-legibility. The shapes are immediately tied to numbers, as a score, or to goals, like breaking the bricks. Especially on a small phone screen, it's easier to read and interact with and cheaper to produce.

So now we've discovered that just asking for abstract images doesn't change much. Maybe what we want is closer to what Bo Ruberg describes in Video Games Have Always Been Queer, an abstraction of not just the visuals but also of the play mechanics. Ruberg's book lists many ways people have always played games queerly, against or in excess of what the developers intended. However, the book focuses on reading and playing games. As a design methodology, "allow players to do what they want" isn't particularly actionable. That is what the most popular games like Minecraft, Skyrim, Roblox, or Zelda are doing and is the selling point of the "web 3.0 metaverse" that nobody actually wants. The slippery nature of queerness makes it an impossible foundation to build a solid work on. While it's a useful signpost, we need something more concrete.

There is a method in game design called greyboxing where games are designed as blank stages so that the gameplay can be developed separately from the more cosmetic elements like visuals and sounds. Levels are designed with the default gray cubes that act as spatial placeholders for play to happen inside of. The inevitable message of this tool is that what your game looks like doesn't matter as much as the gameplay does. Super Mario Bros doesn't hinge on being fun to play because of the green pipes and red hat, it's fun to play because of the level design and way you can move, jump, run, and shoot fireballs. Visuals help clarify these designs by quickly communicating what's at hand for the player to react to. After that, you get to the "art" layer and create likable characters and environments. From the perspective of considering a videogame first as a game and as a way to run an industry that requires highly specific division of labor this process is necessary and logical.

But videogames are not just games, they are also visual art, music, and theater. Videogames have always been played queerly and they have always been these other art forms, however much they get ignored or deprioritized by the game industry. People have taken games to these other polarities like JODI's websites and installations, Theo Triantafyllidis's mixed reality theater, and Tammy Duplantis's GameBoy concert music or can be somewhere in the middle, like David Kanaga's Oikospiel. Again, my goal is not to say that the dominant way is bad I just want to see where else we can go.

What the process of greyboxing reveals is that while you can wait to put 'art' or 'music' in a game you need the audio-visual feedback to have a videogame at all. Otherwise you just have a hypothetical set of ideas running in code on the computer. Visuals and sound communicate affordances to the player so that they can orient themselves in the game space and understand their potential responses to it. Representational visuals are a useful shorthand for this, if you see a gun you know you can shoot it. But what if the screen just had a cube? Or a color? What can you do with a word?

Suddenly a chasm of potential has opened up. When presented with an abstract image and given no concrete goal all you can do is start hitting buttons and see what happens. Even if you guessed what would happen, like an up arrow key moving a shape forward, it's surprising. There's a playful joy reintroduced, or maybe uncovered, in simply pressing a button and receiving a response. Where do you go from there? It becomes an open dialogue between player, designer, and game. Which, again, this is always present. But here it's especially true. There is no stated goal to fall back on. The goal is to play and to feel.

We've arrived at an understanding of abstraction that hinges simultaneously on ideas from modern art and from queer games. It's the kind of abstraction that Brian Massumi, writing in the wake of Deleuze, calls the virtual. This is different from the virtual we usually mean to just mean "digital". This virtual is about potential and the far end of consciousness, something that just barely exists enough to be barely, maybe perceived as a glimpse but is not yet concrete. The representational videogame object is maybe the opposite of this. When you see a gun in a game you know what a gun is, what it's for, and how to use it. And it does what you expect. All of its explosive potential to be anything else has been drained into this straightforward functionality. There is no uncertainty. The virtual is the other direction… there are elements in proximity to each other but the ways they interact has yet to be determined.

A more concrete explanation of this is Sara Ahmed's queer use, which, like Ruberg's queer play, is about objects being used in surprising ways based on need and desires, like a bird making a nest in a mailbox. What else could be done with the virtual gun? Hit something with it, use it to prop something up and build with it, melt it down and use it for parts, use it for decoration, lick it, use it as a dildo (or as an actual dick…). There are many potentials. Us recognizing it as a gun sets up expectations and associations, but, like any object in our consciousness, it can suddenly be revealed as a construct and fly back into abstract, virtual potential.

While using objects queerly gets us moving toward the virtual, abstract images naturally live much closer. We recognize cube shaped objects in the world but there is no natural object we would say is -just- a cube. We know it's a mathematical, platonic concept that we were taught and then apply as an adjective to things that fit. It offers some affordances, like stackability, but doesn't immediately suggest a hyperspecific use. When presented with a simple shape one of our primary instincts is to play with it.

Another thing abstraction affords the artist/developer and the viewer/player is emotional space. Writers like David Getsy, Zachary Rawe, William J. Simmons, and Amy Silman have shown how working in forms developed in modern art have allowed for queer artists to work through issues that are difficult to articulate in representational art, including ideas that are subconscious or that feel unsafe to express. This space allows for ideas to be expressed in ways invisible to outsiders through oblique references and evoking ambiguous yet specific feelings. For me it also speaks to feelings of alienation.

It also helps me feel less alienated to game design in general, which typically demands a team of people with specialized roles in programming, art, music, marketing, and so on to make and release a game. Abstract games don't have to line up to the virtuosic expectations of realism in videogames. Abstraction is "too easy", but making art is not about doing something just because it's hard. You can let go of any part of the process if you don't want it! It also brings the materiality of computer graphics to the forefront, since our brains are not distracted by easily classified image objects. What's deciding how these shapes and colors are being rendered to the screen? The answer lies somewhere between the artist, game engine, computer, screen, manufacturer, your room, and yourself.

The abstract art complaints: "I could have done this!" "My child could have done this!" Yes! Exactly! You could do this. You can make games too. It doesn't require you to get a special degree or spend years developing a game alone in your spare time. You could make one this afternoon. Videogames are an art you can actively participate in as easily as you can go to the store and buy some paint. Ok, it's slightly more than that since pencils and paint have an immediacy of applying pigment to a surface, but videogames can be simple too. You can experience the joy of working with the software instead of fighting against it in the name of realistic representation. And then you'll wonder why we are stuck on making games with guns.